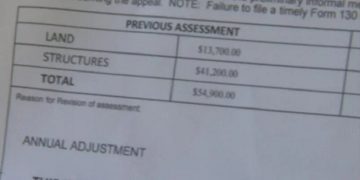

Based on the raw numbers, Monroe County, Indiana, shows an apparent racial and ethnic disparity in COVID-19 vaccination rates.

That disparity starts to shrink, but not necessarily disappear, if the analysis accounts for differences in age distribution for different racial or ethnic groups in the county.

Based on data from Indiana’s department of health, just 1.70 percent of those who are fully vaccinated in Monroe County so far are Hispanic (284 of 16,667), compared to 3.55 percent of Hispanics in the general population. But based on 2019 estimates from the US Census, Hispanics make up just 1.52 percent of the county’s population that is older than 50.Reacting to potential racial disparities in COVID-19 vaccination rates, activist Vauhxx Booker told The Square Beacon it’s important to account for the age distribution, because that affects the kind of narratives that get told about the differences in vaccination rates.

The age distribution of race and ethnicity matters, because up until just recently, it has been just older Hoosiers—other than front-line health care workers—who have been eligible for the vaccine. For the last couple of weeks, the eligibility age bracket has included only those 50 and older.

As of Monday in Monroe County, 75 percent of those who are fully vaccinated are older than 50.

If the 50+ universe is taken as a measuring rod for disparity, even if it might be imprecise, then the Hispanic population is actually “overrepresented” among the vaccinated—by 0.18 points.

Tuesday’s news that those as young as 45 are now eligible for the COVID-19 vaccination could mean that disparities in raw numbers could start to level out more.

Based on Monday’s numbers, just 1.43 percent of those who have been vaccinated in Monroe County are Black (239 of 16,667), compared to 3.72 percent in the general population. But Blacks make up just 2.19 percent of the county’s 50+ population. That’s still a 0.76-point difference between 1.43 and 2.19—but it’s smaller than the 2.29-point gap for the general population.

Either of those differences could be covered by the number of people of unknown race who have been vaccinated so far: 2.32 percent. It’s not required for people to give their race when they get vaccinated.

It’s a similar story for the Asian population. Of those vaccinated in Monroe County so far, 2.02 percent are Asian, compared to 7.3 percent of Asians in the general population. But Asians make up just 2.68 percent of the 50+ population.

To illustrate the difference in possible narratives, Booker points to the raw numbers of vaccinations for whites. In Monroe County so far, 91.5 percent of those vaccinated are white. That’s more than the 85.95 percent of whites in the general population.

But whites make up 93.96 percent of the 50+ population in the county. So whites could be analyzed as getting vaccinated currently at a rate that is 2.46 points lower than expected, compared to their representation in the 50+ population. It’s a difference that might be framed with a narrative about the “willingness” of whites to be vaccinated, Booker says.

When disparities in vaccination rates are identified, Booker told The Square Beacon, that can serve a message that urges Black people to go get vaccinated. There’s an “element of blame and shame” that becomes a part of news headlines, Booker said.

There’s a subtle, but important difference between saying that Black folks aren’t going out and getting the vaccine, and that Black folks aren’t receiving the vaccine, Booker said.

A recent NPR poll indicates that there’s about the same hesitancy among Black and white Americans for getting the vaccine.

“You can put the emphasis on Black folks—that we need to go get vaccinated,” Booker said. He added, “Really, the blame might be better spread to the medical community, and making sure that we are reaching out to underserved populations, to make sure that they’re receiving adequate health care.”

Distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine to underserved populations has been the focus of a working group, formed by Monroe County’s health department, which includes Booker.

Some of the working group’s efforts were highlighted for the board of health by Monroe County’s chief food sanitarian, Nicole Wagner, at the board’s meeting last week.

Wagner said an intern has been hired to help compile the data on vaccination numbers in underserved populations. A handout with general vaccination information is being created in English and Spanish that can be passed out to various community groups and posted on social media outlets, Wagner said.

Among the community groups that have been identified, according to Wagner, are some after-school programs. Children are sometimes the communicators for their household, based on language barriers, Wagner said.

Wagner also reported to the board of health that she had given a presentation at a meeting of the NAACP to talk about general vaccination information and COVID information for the community. The working group has also partnered with staff at Indiana University to reach different minority groups and underserved population groups within the university, Wagner said.

Wagner also said the health department’s COVID-19 web page is getting translated into Spanish—that work is underway. Wagner also said the group is looking to work on sustainable goals that can continue past the COVID-19 pandemic.

The board’s strategic plan, Wagner said, would be used to work towards those goals.

At its meeting last week, the board adopted a new five-year strategic plan, which includes a section on addressing racial disparities in health outcomes.

A goal listed out in the plan says: “By 2021, partner with Community Justice and Mediation Center and community partners to identify ways of connecting and contributing to efforts that address racism, ethnic disparities, and health inequities in Monroe County.” There are six different action steps in the strategic plan that are meant to help achieve that goal.

At previous weekly Friday press conferences on COVID-19 response, county health administrator, Penny Caudill, has talked about the possibility of reaching out to underserved communities not just with information, but with vaccine. That will depend on an allocation by the state health department of the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine.