Monroe County, Indiana – Monroe County attorneys and judges are scrambling to figure out how the newly enacted federal moratorium on evictions applies locally. Some worry the moratorium will only delay evictions, rather than prevent them.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a temporary halt in evictions from Sept. 4 through Dec. 31 in an effort to curb the spread of COVID-19. Keeping people in their homes allows for easier self-isolation for sick or immunocompromised people, according to a notice about the CDC’s order. Homelessness increases the likelihood of people moving into group settings like shelters, increasing their risk of exposure to the coronavirus.

“Not being evicted is better for the overall health of the community,” said Tonda Radewan, coordinator of Monroe County’s Housing Eviction Prevention Project.

The executive order doesn’t exempt tenants from paying their rent. In January, landlords can file for eviction if tenants haven’t paid the total amount owed.

Monroe County Circuit Court Judge Catherine Stafford is one of two judges who presides over eviction hearings. She said the county usually sees about 700 to 800 evictions per year, but this year there have only been a couple hundred from before March and few others after. Since the pandemic took hold, the court has been hearing emergency cases, such as instances involving domestic violence or threats of violence against the landlord.

Stafford said if Monroe County tenants are covered under the CDC order and fill out the declaration form, their eviction hearing will likely get pushed to January.

“January is going to be busy,” she said.

Diane Walker, executive director and attorney at District 10 Pro Bono Project, said a government program for rent assistance would be more effective in preventing evictions.

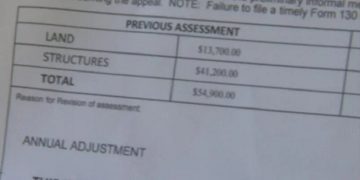

Both landlords and tenants are in tough positions, Walker said. Mom and pop companies don’t want to kick good tenants out just because they can’t pay rent, but the landlords need to pay property taxes and maintenance costs. And the economic crisis isn’t tenants’ fault. She referenced the statistic that somewhere between 50% and 78% of Americans lived paycheck to paycheck before the pandemic, according to The Washington Post. Almost 3 in 10 adults have no emergency savings at all, according to a 2019 Bankrate survey.

“Everyone is kind of stuck,” Walker said.

She said she expects many people to lose their housing after the moratorium ends, and it can be hard to find a new place in Monroe County. The median rent in the county is about $893, compared to the median rent in Indiana of $825.

“If they can’t afford their apartment now, it could be very hard to find somewhere else to move in,” Walker said.

Forrest Gilmore, executive director of Shalom Community Center, said homelessness isn’t always immediate because people tend to exhaust their personal resources before going to a shelter. They might dip into an emergency fund or stay with family members or friends.

Gilmore said he thinks the moratorium allows for some catchup, but it’s not enough. He said there needs to be more government assistance for people to recoup lost income.

Jamie Sutton, executive director and attorney at Justice Unlocked, said the CDC order has the same problems as the moratorium under the federal CARES Act and Gov. Eric Holcomb’s now-expired moratorium. They didn’t include rent forgiveness or rent freezes either. There are local resources for rent assistance, Sutton said, but many could be easily overwhelmed.

Sutton said it doesn’t seem like tenants hundreds or thousands of dollars behind on rent will be able to catch up before the CDC order ends, considering the economic fallout from the pandemic.

“Most tenants, especially if they’ve lost their job or had a reduction in income due to COVID-19, if they don’t have the rent now, they won’t have it four months from now,” Sutton said.

Sutton said everyone is still trying to understand the eviction moratorium, and it’s frustrating that the rules are changing so often as new agencies issue their own orders.

“Our response as a society seems reactive rather than proactive,” he said. “There’s never going to be a perfect plan for responding to a pandemic, but I think we’re failing to plan for things that are very foreseeable.”