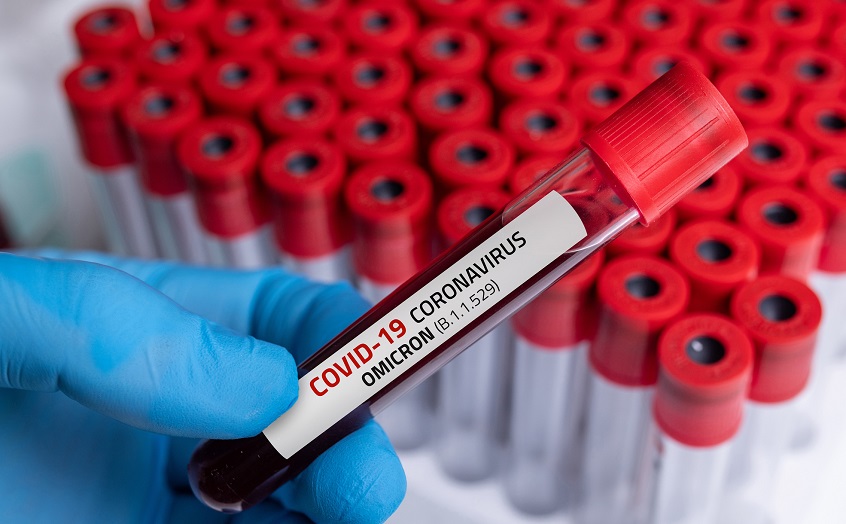

As we approach the winter, the fear of a new Covid-19 wave is increasing. Winter waves occurred last winter and the winter before. People will spend more time indoors and will gather more frequently during the upcoming holidays. What makes the upcoming period different from past years is the rate of Covid-19 vaccination, which surely helps in reducing the number of new Covid-19 cases and the symptoms that infected people might develop.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention data, more than 80 percent of Americans are now vaccinated with at least one dose of the vaccines, while 68.4 percent have completed the primary series of the vaccines. With such high vaccination rates, America shouldn’t have to worry about another winter wave this year. However, the Omicron variant of the virus is known to be very good at avoiding both vaccination and natural immunity.

The Omicron variant was the first strain that was able to infect immunized people at high rates. That prompted the major vaccine providers to work and develop specific vaccines that were expected to offer better protection against Omicron. Since the majority of Americans had already been vaccinated with one, two, or three doses when the Omicron-specific vaccines were revealed earlier this year, the newly developed vaccines have been offered as a fourth dose.

However, two recent studies show that the Omicron-specific vaccines offer similar protection just like the original vaccines. The studies are comparing the immune responses of people who received the regular fourth dose and those who received the fourth dose of the Omicron-specific vaccines. And they found no significant differences. The first study was conducted by Columbia University and the University of Michigan, published Monday. A Harvard University–affiliated paper released Tuesday came to the same conclusion: that the original vaccine and the updated booster performed very similarly.

Studies have found that both the original and the bi-valent vaccines create strong immune and antibody response which will reduce the severity of the infection for those infected with the virus. However, none of the vaccines were able to initiate the part of the immune response that is responsible for infection prevention, meaning that the vaccines are very similar.

A phenomenon called “immune imprinting” might be the reason for the results in the recent studies. This phenomenon happens when a past infection might prevent the immune system from providing a different response when it “gets in touch” with another variant of the same virus. Last year, scientists warned that constantly updating the vaccines might not be very beneficial, citing the “immune imprinting” phenomenon.

“All those things push and pull your immune repertoire, your antibodies and things in different directions, and make you respond differently to the next vaccine that comes along […] So that’s what’s called immune imprinting,” Prof. Danny Altmann, professor of immunology at Imperial College London explained to Medical News Today in an interview earlier this year.

Although Pfizer and Moderna only submitted data from mice, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of the new boosters just like they did with the initial vaccines, through an emergency use authorization. So far, none of the vaccine producers has publicly released human data. The interest in the new, bi-valent vaccine is still low even though everyone 12 and older is eligible for the booster if they’ve received their primary shots.