A recent infusion of Indiana alums into the MLB ranks has certainly been noticed back in Bloomington.

“It does create such a great positive energy and excitement around the program every day,” IU coach Jeff Mercer said, “when you are flipping on the TV and you are watching Kyle Schwarber and you’re watching Kyle Hart and you’re watching Jonathan Stiever.”

It’s a welcome development for a program that sent 29 alums to the majors from 1902 to 2017. That’s one player every four years. But in 2020, Hart debuted in Boston, Stiever in Chicago, and Caleb Baragar in San Francisco. Aaron Slegers has reemerged in Tampa, heading into the postseason this week.

Along with that pitching quartet, there is the slugging duo of Schwarber and Alex Dickerson. Suddenly, IU’s MLB circle isn’t so small.

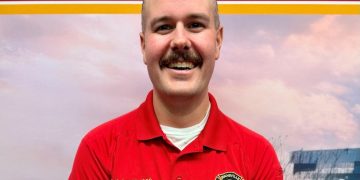

It’s something Mercer, the Hoosiers’ third-year coach, will minimize from a personal standpoint. His predecessors, Tracy Smith and Chris Lemonis, recruited and developed these players. From a program perspective, though, Mercer isn’t going to discount the MLB surge.

“The excitement it brings our players, knowing players from our program have had such success, it is now the expectation of being able to advance and have success at the highest level,” Mercer said.

In the last decade, IU has proven it can be a national contender and develop pros. Mercer believes he can build more because — to cornily borrow a line from The Six Million Dollar Man — the Hoosiers have the technology.

Engage the 2019 Big Ten Coach of the Year in a discussion about player development, and he will gladly talk about spin rates on fastballs and launch angles off bats. Mercer will mention the Edgertronic Camera they use to analyze a swing at thousands of frames per second. They are pulling TrackMan data onto a dashboard, breaking down exit velocity by pitch, by quadrant, and by count.

IU’s current pro contingent has certainly been guided up the ranks by similar datasets, because tech has pervaded the game in the last handful of years. Since 2018, Mercer and his staff have been building out their own capabilities, trying to stay ahead of the curve. But carefully so.

“For us at Indiana, having all the resources we have, it’s still taken three years to implement what we feel like now is 90 percent of the process we will use moving forward,” Mercer said. “You can’t rush into something you don’t fully understand. Because if you don’t fully understand it, how can you communicate it and how is the player not supposed to be overwhelmed?”

Mercer calls it a “crawl, walk, run” approach. He wants to understand every methodology they employ, because this is more than just for show. Like a class in advanced calculus, the Hoosiers will learn the meaning behind hundreds of data points, informing every decision the coaching staff and the athlete make about changes in technique and approach.

This, they hope, will offer an edge in developing pros.

Number-crunching isn’t a new concept in baseball. In the early 21st Century, the Oakland A’s became the posterchild for “Moneyball.” But the push to identify “value” in players naturally transitioned into an arms race to grow it. Private companies have developed slo-mo cameras to analyze flawed swings. They have found ways to measure spin rates and break paths on pitches.

These tools were eagerly adopted at all levels. The pros want to maximize growth in their minor-league systems. Colleges want to prove they are just as capable — if not more so — developing high schoolers into prospects.

And they can do it faster.

“Seven years ago, you gave us a player, I could give you a professional in three or four years. But now … it’s can you teach him what he needs in six months to a year?” Mercer said. “Because now you have a ton of these kids who are draft eligible sophomores. How quickly can you help a kid be able to get to where he wants to get to?”

IU appears up-to-pace. In a COVID-shortened 2020 season, IU’s leaders in batting and earned run average were both sophomores, outfielder Grant Richardson and pitcher Gabe Bierman. The expectation is to continue attracting high-ceiling talents, like former Southern Cal signee, shortstop Tank Espalin, who flipped to the Hoosiers late in the 2020 cycle.

Espalin, rated as a future high-round draft pick by recruiting services, cited the IU coaching staff’s “hands-on” approach as a reason he landed in Bloomington.

“When I was a player, there was nothing more frustrating than a coach saying ‘Hey, I think we should do this.’ … Is this something you were up all night thinking about and studying and analyzing or is this, like, a decision you made in the last five minutes? This is my career and this is a really big decision,” Mercer said. “With my players, I try to think the same way. If we’re going to suggest something, it’s rooted in science, it’s rooted in data.”

To the layman, so much talk of vertical and horizontal break on pitches, or launch angles on line-drives, may be hard to absorb. But this is a language players like Baragar, Slegers, and Schwarber have mastered.

Any pro has to. So every Hoosier will.

“We go into our pregame planning, I’ll talk about the spin profiles of all the pitchers we are going to face, vertical-induced break, horizontal action, arm slots, hand placements,” Mercer said, listing quite a few more. “What I tell those guys is ‘Listen, if you want to play at the next level’ — which they all do — ‘this is just the prerequisite.’ You have to be able to speak this language.

“If they leave our program with no foundation in that, we are setting them up for failure.”

In the end, Mercer just wants to recruit “successful” people with the right work habits. IU’s recent crop of MLBers fits that mold. Slegers was a 6-foot-10 walk-on who turned into a fifth-round draft pick. Now he just posted a 3.46 ERA as a reliever for a playoff squad. Baragar, a junior college product, spent two years in Bloomington, bounced around the minors, then surprisingly made the Giants this summer. He ended up, as a reliever, leading the Giants in wins with five.

Dickerson battled injuries early in his MLB career. This year, he hit three home runs in a game for the Giants, tying Willie Mays’ club record for total bases in a contest.

They were all humbled by the game. They each worked hard enough to overcome it.

“Baseball doesn’t care who you are or where you came from,” Mercer said. “When it’s just pure competition and your fortitude and you’re competitive, those guys have shown over and over again that they are just tough enough and they have worked enough to advance.”

“Obviously, it’s a testament to Tracy and Chris and the players that came before, and we’re starting to see the fruits of those labors on almost an annual basis now.”

Now it’s just about continuing a trend line.

“I don’t have any doubts, in due time, the players we are able to recruit and coach,” Mercer said, “they will go on to have successful personal lives and careers and, hopefully, some of them happen to be in baseball, and they can advance themselves. It’s certainly always the goal for us to become and to be the most comprehensive player development program in the country.”